Parametric oscillator: a close look

This post contains my research notes about the parametric oscillator. Here is an introduction from Wikipedia (see references section):

A parametric oscillator is a harmonic oscillator whose parameters oscillate in time. For example, a well known parametric oscillator is a child pumping a swing by periodically standing and squatting to increase the size of the swing's oscillations. The varying of the parameters drives the system. Examples of parameters that may be varied are its resonance frequency and damping .

As that Wikipedia article shows, a certain coordinate change can eliminate damping. So we focus on the case where there is only a resonance frequency , which varies with time. That is, we consider the differential equationwhere repeats itself after some time interval .

The main purpose of this post is to preserve what I learned, for my own future reference. I am bad at maintaining handwritten notes, so I am moving to a digital medium. On the off chance that this interests others, I put it on the web. This post contains some work of my own that goes beyond the material in the references section. Most or all of my findings are likely known by experts. The proofs are mine, and so are the mistakes.

Floquet theory

A suitable mathematical background for the parametric oscillator is Floquet theory (see references section). It deals with linear differential equations of the form where , and the function is periodic with . We could also consider complex numbers as the elements of and , but we shall stick with the reals here, in accordance with the physics. We can write a parametric oscillator as a Floquet equation:

I encountered Floquet theory in the well-known "Mechanics" book by Landau and Lifshitz (see references section), which we shall call "the book" in this post. The book contains a chapter on parametric resonance, which deals with parametric oscillators and their resonance behavior. The book uses Floquet theory in specialized form, without calling it so. Part of my motivation here is to obviate the exact way in which that book chapter ties in with general Floquet theory.

The monodromy matrix

We shall now introduce the notion of monodromy, which is pivotal for Floquet theory. Let be a fundamental matrix for a Floquet differential equation. Then is also a fundamental matrix, because . So we have for some invertible -matrix . This describes the change of the solution after each period. It is called the monodromy matrix. Rightly so, since in Greek "mono" means "one" and "dromos" means "course" or "running".

One checks easily that different for the same can yield different . But:

Lemma: The monodromy matrix of a Floquet equation is determined up to isomorphism.

So see this, let be another fundamental matrix for . Let be the corresponding monodromy matrix. We have for some invertible -matrix . So

Because and are invertible, we get □

Importantly, it follows that any two monodromy matrices have the same Jordan normal forms, and therefore the same eigenvalues.

Now recall that we assumed that the matrix from our Floquet equation has only real entries. Naturally, we are only interested in real solutions . So any resulting too has only real entries.

Floquet's theorem

Floquet equations cannot not generally be solved symbolically. However, Floquet's theorem makes a useful statement about the solutions. The version of the theorem that interests me here is:

Theorem: Any fundamental matrix of a Floquet equation with period has the form for some -periodic matrix function and some matrix of matching dimension.

Note that the statement employs the matrix exponential (see references section).

Proof: Because is invertible, it has a matrix logarithm (see references section), that is, a matrix of which it is the exponential. (Important properties of the matrix logarithm are: they exist for every invertible matrix; and as in the special case of scalar logarithms, they can be complex-valued even if the exponential is real-valued, and they are not unique. For example, is a logarithm of minus one for every integer .) Let be a logarithm of , divided by . That is, . Let . To see that is -periodic, consider

Applying the theorem to the oscillator

First we perform a coordinate change into the eigensystem of the monodromy matrix . This is tantamount to assuming that is in Jordan normal form. As for any -Matrix, the Jordan normal form is where the are the eigenvalues and is zero ore one. The book considers only the case where the two eigenvalues differ, and therefore is zero. We shall also consider the case where is one. This can happen, as we shall see later.

We shall now apply the Floquet theorem. First, we need a logarithm of . We shall deal first with the more difficult case where is one, and therefore .

As explained in a Wikipedia article referenced below, the logarithm can be calculated as a Mercator series:We have where stands for the identity matrix, andUsing the fact that vanishes for greater than two, we getFrom the proof of the theorem, we know that we can choose . Some calculation involving the matrix exponential yieldsNote that , as required. Now suppose we have a fundamental matrixWhen we spell out the Floquet theorem elementwise, and ignore the , we get:

Corollary: If , there are -periodic functions , and such that

If , we get the result from the book:

Corollary: If , there are -periodic functions and such that

The calculation is much simpler than for . I leave it away here.

Possible eigenvalues

First, we observe, like the book:

Corollary: The eigenvalues of the monodromy matrix of a parametric oscillator are either real or complex conjugates of one another.

This follows simply from the fact that has only real entries. Now the book deduces, for , that the eigenvalues must be mutually reciprocal. We shall show this even for :

Lemma: The product of the eigenvalues of the monodromy matrix of a parametric oscillator is one.

Proof: Liouvilles formula (see references section) entails for every fundamental matrix of a Floquet equation thatHere stands for trace, which is the sum of the diagonal elements of a matrix. For a parametric oscillator, that trace is zero. So is constant. Because , we have . Since is constant, we have , and since we have . The claim follows because the determinant is the product of the eigenvalues □

Combining the results of this section, we see that the eigenvalues are either reciprocal reals, or two non-reals on the complex unit circle which are complex conjugates of one another. When , we know also that the two eigenvalues are the same, and so they are both one or both minus one.

Classification of possible behaviors

First, suppose that . Then the eigenvalues are both one or both minus one.

If , we have by an earlier corollaryfor -periodic , , and , where and are coordinates which go along with the eigensystem of the monodromy matrix.

If , we haveNote that this entails that we have -periodic , , and such that

Now suppose that . We concluded above that and for -periodic and .

If the eigenvalues are both one, we have -periodic behavior, respectively. Note that in this case is not just isomorphic to, but equal to the identity matrix. So any coordinate system is an eigensystem, that is, we can choose the freely.

If the eigenvalues are both minus one, we have -periodic behavior. In this case is not just isomorphic to, but equal to minus one times the identity matrix. So here too, any coordinate system is an eigensystem, so we can choose the freely.

If the eigenvalues are other reals, the one whose absolute value is greater than one "wins" as goes towards infinity. So the amplitude grows exponentially. If the eigenvalues are not reals, they are on the complex unit circle, and the amplitude has an upper bound.

Example: the Mathieu equation

The Mathieu equation is the parametric oscillator withIf this came from a child on a swing, it would be a strange child: one that stands and squats at a frequency independent of the resonance frequency of the swing. Still, the Mathieu equation is important in physics.

Here is a graph showing the monodromy's eigenvalues for the Mathieu equation with and . The vertical axis corresponds to , which ranges from to . Horizontally, we have the complex plane. For each , the graph contains both eigenvalues of the corresponding monodromy matrix. I refrained from drawing the coordinate axes, to avoid clutter.

The eigenvalues of a Mathieu equation as gamma changes

The graph shows that, for every , the eigenvalues are either (1) on a circle, which happens to be the unit circle, or (2) opposite one another on a perpendicular of the circle, actually, reciprocal reals. This agrees with our mathematical results about the possible eigenvalues. In case (1) we have no resonance. In case (2), we have resonance.

The greatest resonance is represented by the "face of the bunny", around , connected to the circle at . The second greatest resonance is represented by the bunny's (uppermost) tail, around , connected to the circle at . This second greatest resonance corresponds to a normal child that stands and squats once during a period of the swing. The greatest resonance corresponds to an eager child that turns around at the apex, facing down again, and stands and squats again on the way back.

There are also resonances for smaller , their connection points with the circle alternating between and .

It is worth noting that, for smaller , the resonance areas can shrink in such a way that only the bunny's face at remains, while all resonances at smaller vanish. That is: if the child's standing and squatting have a small amplitude , the child needs to stand and squat more often to achieve resonance.

The transition into and out of resonance

Possible shapes of the monodromy matrix

As we have seen, the transitions into and out of resonance happen where the eigenvalues are both one or both minus one. This means that the Jordan normal form of the monodromy matrix iswhere is zero or one. So:

To fully understand the transitions into and out of resonance, we must know !

From the start, I wondered about the case where cannot be diagonalized, that is, , since that was left aside in the book. Next, I was intrigued by the instantaneous ninety-degree turns where the bunny's body meets the face or a tail. Those points turned out to be the only ones where might be undiagonalizable. So I kept running into the question about .

I checked, with Mathematica, the bunny's two transition points for the resonance at , and its two transition points for the resonance at . In all cases, we have . So the question arises:

Is it true for all parametric oscillators that the monodromy matrix is undiagonalizable at all transitions into and out of resonance?

We shall now shed light on this question.

The meaning of diagonalizability and lack thereof

First, suppose that . If , we have, as observed above, two linearly independent solutions and where the are -periodic. Since every solution is a linear combination of those , it follows that every solution is -periodic. So, for every initial phase at some , the corresponding solution is -periodic. If , we can deduce by a similar argument: for every initial phase at some , the corresponding solution is -periodic.

Now suppose that . If , we have, as observed above, two linearly dependent solutions and where the are -periodic. So the solution space, whicTh is two-dimensional, has a one-dimensional subspace of -periodic functions. All other solutions grow linearly with time. So for every , the (also two-dimensional) space of initial conditions at has a one-dimensional subspace of -periodic solutions. For all other initial conditions, the solutions grow linearly with time. For , we get something similar: for every , the space of initial conditions has a one-dimensional subspace of periodic solutions, this time with period . Again, all other solutions grow linearly.

In summary: for , all solution are periodic, while for only some are periodic. In the latter case, we can destabilize a periodic solution by arbitrarily small changes of the initial conditions.

Undiagonizable examples

We shall now give a stringent example, more illuminating than the Mathieu equation, where , that is, cannot be diagonalized. Here will be a certain rectangular pulse:

Here is the period, which we must still determine. And is a value greater than one, which we must still determine. For the construction, we assume temporarily as initial conditions and . That is, the solution is the cosine for . We let for a small . The "accelerates the swing", that is, the solution increases its descent more than a cosine while lasts. We choose in such a way that at the solution's first derivative is minus one. There it remains until since is zero there. We let be the point where the solution is zero for the first time for positive . So, from , the solution is again a like cosine with amplitude one, but shifted a little to the left. We let be the time, slightly less than , where the solution is zero the second time for positive . Obviously, the solution is periodic with . It looks like a cosine, except that in the first quadrant there is a "fast forward" lasting from to .

So, our constructed parametric oscillator has a periodic solution. But are all solutions periodic? No! We fine-tuned so that it would have a periodic solution specifically for the initial condition and . As can be easily checked, that there are other initial conditions with non-periodic solutions. So, owing to earlier observations, the initial conditions with periodic solutions form a one-dimensional subspace. That is, the only periodic solutions arise from initial conditions that are scalar multiples of . The period of our function happens to agree with that of the oscillator's solution, so the eigenvalues are one. In summary, our constructed parametric oscillator has

Our constructed supplies one impulse in the first quadrant of the movement. So four quadrants pass between impulses. Obviously, we could modify our construction to have an impulse in the first and third quadrant. Then two quadrants would pass between impulses. So the solution's period would be twice that of , and the eigenvalues would be minus one. We could also modify our construction to have six quadrants between impulses (eigenvalues minus one), or eight (eigenvalues one), or ten (eigenvalues minus one), and so on.

Diagonalizable examples

First I conjectured, in this post, that there is no parametric oscillator with non-constant that has or . My conjecture was inspired by the previous section. But John Baez proved me wrong.

First, an example where . Consider the following non-constant :

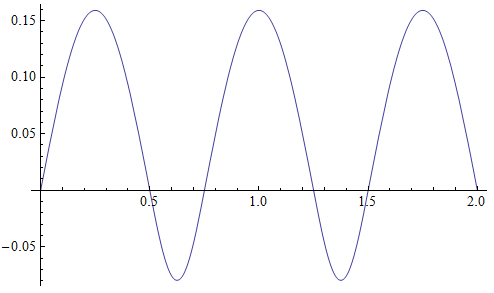

The solution for and is composed of two sine curves of different frequency:

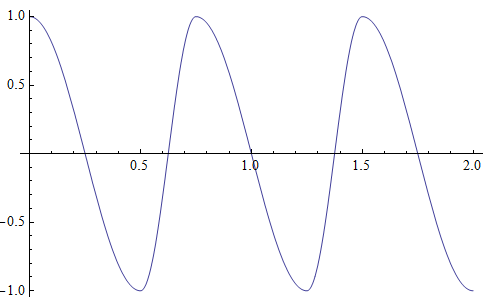

It is periodic, with period . The solution for and is composed of two cosine curves of different frequency:

This too is periodic with period . Since the solution space is spanned by those two solutions, every solution is periodic with period . Since is also the period of , both eigenvalues are one. So the monodromy matrix is the identity.

Now an example where . Consider the following non-constant :

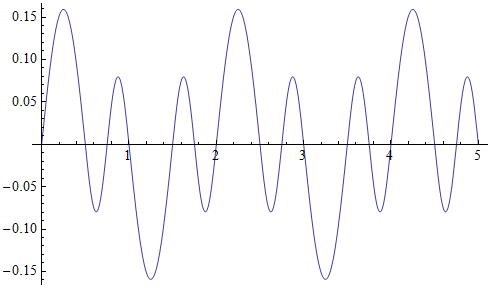

The solution for and is composed of two sine/cosine curves of different frequency:

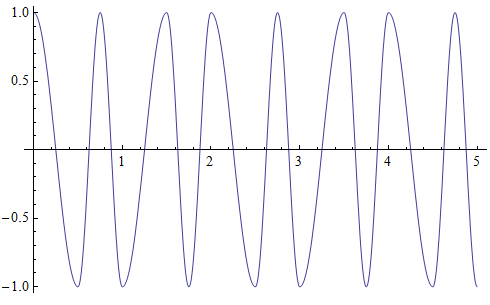

This is periodic, with period two. The solution for and too is composed of two sine/cosine curves of different frequency:

This too is periodic with period two. Since the solution space is spanned by those two solutions, every solution is periodic with period two. Since that is twice the period of , both eigenvalues are minus one. So the monodromy matrix is the minus identity.

References

L.D.Landau and E.M.Lifschitz.Lehrbuch der theoretischen Physik I: Mechanik.Verlag Harry Deutsch, 14. Auflage.

Wikipedia: Floquet theory

Wikipedia: Liouville's formula

Wikipedia: Matrix exponential

Wikipedia: Logarithm of a matrix